Rabbi Yitzchak Etshalom has been teaching Torah in his native Los Angeles since 1985. He has produced two volumes of his "Between the Lines of the Bible" series and serves as Rosh Beit Midrash at Shalhevet and Chair of the Bible Department at YULA. This article appears in issue 35 of Conversations, the journal of the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals.

Visiting En-Dor in a Tenth-Century Babylonian Yeshiva[1]

For my dear teacher and friend, R. Hayyim Davidson

- Introduction

The episode at En-Dor, detailed in 1 Shemuel 28, is one of the most puzzling and challenging in all of Biblical narrative. The exegetical challenges are well known, some more than others. They consist of detailed questions of nuance as well as broader, overall issues. I will adumbrate more fully below, but as an example of a nuance problem—why does Shaul request that the necromancer “raise” Shemuel (ha’ali li)—is this an idiomatic phrase or does it reflect something about the location of the spirits of the departed? One of the macro issues to assess is the efficacy of the entire enterprise—which will be the focus of this paper. Do the occult practices, forbidden explicitly by God in Devarim 18 and regarded as abominations, really “work”? Is it possible to communicate with the dead? And, if so, why did God allow Shaul to get reliable information from the spirit of Shemuel—but deny him access through the proper channels of prophecy and visions?

Just surveying the history of exegesis—even if we were to limit ourselves to the traditional commentators, would fill an entire volume. We will focus on one overall issue and that through the lens of two of the leaders of Babylonian Jewry in the tenth century. In order to understand the problems that they were addressing, we will first present the narrative.

- The Text

Where necessary, I will transliterate words or phrases, otherwise, this English translation is taken from the “old” JPS translation (1917), with some minor modifications.

1) And it came to pass in those days, that the Philistines gathered their hosts together for warfare, to fight with Israel. And Achish said unto David: 'Know thou assuredly, that thou shalt go out with me in the host, thou and thy men.'

(2) And David said to Achish: 'Therefore thou shalt know what thy servant will do.' And Achish said to David: 'Therefore will I make thee keeper of my head for ever.'

(3) Now Samuel had died (uShemuel meit), and all Israel had lamented him, and buried him in Ramah, even in his own city. And Saul had put away those that divined by a ghost (ovot) or a familiar spirit (yidonim) out of the land.

(4) And the Philistines gathered themselves together and came and pitched in Shunem; and Saul gathered all Israel together, and they pitched in Gilboa.

(5) And when Saul saw the host of the Philistines, he was afraid, and his heart trembled greatly.

(6) And when Saul inquired of the Lord, the Lord answered him not, neither by dreams, nor by Urim, nor by prophets.

(7) Then said Saul unto his servants: 'Seek me a woman that divineth by a ghost, that I may go to her, and inquire of her.' And his servants said to him: 'Behold, there is a woman that divineth by a ghost at En-dor.'

(8) And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and went, he and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night; and he said: 'Divine unto me, I pray thee, by a ghost, and bring me up (ha’ali li) whomsoever I shall name unto thee.'

(9) And the woman said unto him: 'Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that divine by a ghost or a familiar spirit out of the land; wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?'

(10) And Saul swore to her by the Lord, saying: 'As the Lord liveth, there shall no punishment happen to thee for this thing.'

(11) Then said the woman: 'Whom shall I bring up (a’aleh) unto thee?' And he said: 'Bring me up Samuel.'

(12) And when the woman saw Samuel, she cried with a loud voice; and the woman spoke to Saul, saying: 'Why hast thou deceived me? for thou art Saul.'

(13) And the king said unto her: 'Be not afraid; for what seest thou?' And the woman said unto Saul: 'I see a lordly being coming up out of the earth.'[2]

(14) And he said unto her: 'What form is he of?' And she said: 'An old man cometh up; and he is covered with a robe.' And Saul perceived that it was Samuel, and he bowed with his face to the ground, and prostrated himself.

(15) And Samuel said to Saul: 'Why hast thou disquieted me, to bring me up?' And Saul answered: 'I am sore distressed; for the Philistines make war against me, and God is departed from me, and answereth me no more, neither by prophets, nor by dreams; therefore I have called thee[3], that thou mayest make known unto me what I shall do.'

(16) And Samuel said: 'Wherefore then dost thou ask of me, seeing the Lord is departed from thee, and is become thine adversary?

(17) And the Lord hath wrought for Himself; as He spoke by me; and the Lord hath rent the kingdom out of thy hand, and given it to thy neighbor, even to David.

(18) Because thou didst not hearken to the voice of the Lord, and didst not execute His fierce wrath upon Amalek, therefore hath the Lord done this thing unto thee this day.

(19) Moreover the Lord will deliver Israel also with thee into the hand of the Philistines; and to-morrow shalt thou and thy sons be with me; the Lord will deliver the host of Israel also into the hand of the Philistines.'

(20) Then Saul fell straightway his full length upon the earth, and was sore afraid, because of the words of Samuel; and there was no strength in him; for he had eaten no bread all the day, nor all the night.

(21) And the woman came unto Saul, and saw that he was sore affrighted, and said unto him: 'Behold, thy handmaid hath hearkened unto thy voice, and I have put my life in my hand, and have hearkened unto thy words which thou spokest unto me.

(22) Now therefore, I pray thee, hearken thou also unto the voice of thy handmaid, and let me set a morsel of bread before thee; and eat, that thou mayest have strength, when thou goest on thy way.'

(23) But he refused and said: 'I will not eat.' But his servants, together with the woman, urged him; and he hearkened unto their voice. So he arose from the earth, and sat upon the bed.

(24) And the woman had a fatted calf in the house; and she made haste, and killed it; and she took flour, and kneaded it, and did bake unleavened bread thereof;

(25) and she brought it before Saul, and before his servants; and they did eat. Then they rose up, and went away that night

- The Problem(s)

There are numerous problems that even a cursory read of the passage brings to the fore. Perhaps the most intractable one is, What actually happened in the necromancer’s house? Are we to believe that necromancy “works” and that it is possible to summon up and communicate with the dead, that they can communicate with us? Besides the question of their having any knowledge worth sharing with us and how they would communicate, the essential problem of the efficacy of ma’aseh Ov sits at the core of this story. For if we believe, as the mainstream of Haza”l clearly did, as well as nearly the consensus of Rishonim, that the forbidden occult practices are effective (some even suggest that they are banned precisely because they work—see Ramban, Shikehat ha’Asin #8—in his appendix to Rambam’s Sefer haMitzvot) then the story has an internal logic, and we just need to fill in the blanks of the mechanics of it all. How do you summon a specific character, what does the character know, how does he/she communicate with the living, what is the role of the medium, etc. If, however, as an admittedly small group of Ge’onim and Rishonim maintain, these practices are all vain, foolish, and without any real efficacy—then how are we to read this story? Perhaps the most elegant and clear presentation of this view is Rambam’s epilogue to the laws of the occult practices:

All of the above matters [divination, necromancy, etc.] are falsehood and lies with which the original idolaters deceived the gentile nations in order to lead them after them. It is not fitting for the Jews who are wise sages to be drawn into such emptiness, nor to consider that they have any value, per: “ki lo nahash beYaakov velo kesem beYisrael: (“No black magic can be found among Jacob nor occult arts within Israel”—Bemidbar 23:23). Similarly, it states “These nations that you are driving out listen to astrologers and diviners; this is not what God…has granted you” (Devarim 18:14). Whoever believes in [occult arts] of this nature and, in his heart, thinks that they are true and words of wisdom but are forbidden by the Torah,[4] is foolish and feebleminded…. The masters of wisdom and those of perfect knowledge know with clear proof that all these crafts which the Torah forbade are not reflections of wisdom, but rather emptiness and vanity which attracted the feebleminded and caused them to abandon all the paths of truth. For these reasons, when the Torah warned against all these empty matters, it advised: “Be of perfect with God, your Lord” (Devarim 18: 13). (Hilkhot Avodah Zarah, 11:16)

This presentation of Rambam’s, which is echoed in passages in the Guide and in several other rulings in Mishneh Torah, is an abrupt departure from the attitude held throughout the rabbinic period, where the reality behind occult practices as well as demonic interactions and the like were both assumed and reported. Regarding the former, perhaps the most well-known report is the Aggadah about the pious man who went to sleep in a cemetery on Rosh haShanah and overheard two dead girls, buried there, conversing with each other about the fortunes of the upcoming year. The one who was able to escape her confines came back with a forecast about agricultural plagues, which the eavesdropper exploited and succeeded (BT Berakhot 18a). The entire story is brought to determine whether or not the dead are aware of what is happening on earth—and the end of the story, in which one of the girls tells the other that people are talking about them on earth, is left as an inconclusive resolution to the question. In other words—the dead continue to exist in some quasi-physical realm, they are able to visit places on earth, gain information, talk to each other, (perhaps) find out what people are talking about on earth, and care about all of that. Given these premises, if there is an effective method to communicate with spirits like this to gain information otherwise unavailable to mortals, people will be tempted to use it. A well-known talmudic story about necromancy itself is the report of Onkelos, before his conversion, who “summoned up” Titus, Balaam, and Jesus to ask them how the Jews were regarded in the “other world” and whether it would be worth joining their nation (BT Gittin 57a).

Rambam’s approach to demonology, magic, and the like was not a revolution of his own making. Two centuries earlier, several of the heads of the academies in Bavel were unabashedly taking the position that “[regarding] the words of our forebears, if they contradict reason, we have no reason to accept them.”[5] A more strident statement with more far-reaching implications for theologically and philosophically limned exegesis is found in a responsum of R. Hai Gaon (939–1038):

We should remind ourselves of the phrases used in the biblical text and to present them before our reasoning, and that which reason allows for from a straightforward reading of the text (“peshat hakatuv”) we will accept and if the matter allows for two or more interpretations, there is no reason to oppose (reject) any of them, rather whichever is closer (to reason) takes priority.[6]

These opinions, expressed in unequivocal terms, were put forth by the leaders of the central academies (metivtot) from where instruction and Torah were disseminated to the entire Jewish world. Bavel’s hegemony lasted until 1038 with the death of R. Hai. There are two startling developments here.

First of all, the teachers of the law and the guardians of the tradition were rejecting the need to accept the validity of earlier talmudic statements regarding things which did not comport with reason; they were even proposing a non-literal reading of biblical texts, where exegetically feasible, where reason was challenged by a straightforward reading of the text. This means that “reason” had become the prime determinant of truth—it was enough to allow an Aggadah to be ignored and it was strong enough to force a new reading of a biblical text.

The second surprise is how little of an impact this entire approach had on the next generations of rabbinic leadership; nearly all of the Rishonim turned their backs on their predecessors and in many cases, ignored their revolutionary approach as if it had never happened.

We will explore the first of these developments, using the exegesis of two of the Geonim to our episode at En-Dor as an example of their method.

R. Saadiah Al-Fayumi

Saadiah ben Yosef al-Fayumi haKohen was born in Egypt in 892 (some maintain 882) and was named to head the Sura academy in Babylonia in 928. This appointment granted him the title “Gaon” which had been the traditional title[7] of the heads of each of the two central academies (Sura and Pumbedita) for several hundred years. He was a trailblazer in numerous areas. He composed the first comprehensive Bible commentary, was a master halakhist as well as philosopher, and his Emunot veDeot remains a staple of Jewish rationalist thinking.[8]

R. Saadiah has the following interpretation of our episode. (This commentary is taken from the commentary of R. Yitzhak Al-Kanazi, a contemporary of Rambam):

I intend to explore five issues:

- Did Shaul think that it was permitted to ask the necromancer to resurrect (?) Shemuel?

- Did Shemuel indeed come back to life or not?

- If he did come back to life, who resurrected him? The witch or Hashem?

- Why did she see him, while Shaul did not?

- Why did Shaul hear him speak, whereas the witch did not hear him?

The answer to the first question is that the text had already testified that Shaul was tormented and occasionally “out of his mind”… such that he would have thought that even an inanimate stone could resurrect the dead, all the more so a necromancer.

As to the second question: The text twice says “Shemuel said to Shaul,” therefore we must understand that Shemuel indeed stood from his grave truly alive. We may not interpret that she was telling Shaul that Shemuel was such-and-such (see below, in R. Shemuel b. Hofni Gaon’s interpretation) and that the text is merely reflecting what Shaul imagined by himself; if so, we would have to call into question every similar passage and every instance of vayomer or vaydaber we would have to interpret against p’shat.

In response to the third question, we must say that the Creator raised Shemuel in order to show his revivification. The text explicitly points out that she asked him “Whom shall I raise?” but it doesn’t credit her with the resurrection itself. It just states “the woman saw Shemuel and she cried out in a loud voice”; if she had been the one to raise him, the text would have explicitly stated “and she raised Shemuel.” If someone asks why the text didn’t state that God resurrected Shemuel, we will answer: It is impossible, based on our reason, for we know that no one is capable of reviving the dead except for the Creator, may His Name be blessed.

Regarding the fourth question, the text never states that Shaul didn’t see Shemuel from the beginning of the story until the end. It merely points out that [he asked] as soon as Shemuel arrived; had he waited until Shemuel arrived, he wouldn’t have asked her “what does he look like?” once he approached and he saw him, he wouldn’t have needed to ask her, but he was hasty to ask her.

The answer to the fifth question is that there is no mention in the text that Shaul heard his words and that the woman was present but didn’t hear. There is no doubt about this whatsoever; but when Shaul and Shemuel met each other, the woman distanced herself a bit from the two of them, went out and left them by themselves while they were talking with each other. She behaved this way per proper protocol. This is the reason that the text states “she came to Shaul and behold he was sore affrighted.”

Discussion

The first thing that we notice about Saadiah’s interpretation is that his frame of reference is resurrection. The only way that he imagines the scene is to picture Shemuel appearing in his body—which is why Saadiah insists, in no uncertain terms, that both Shaul and the necromancer both saw and heard Shemuel. This is a departure from the approach taken in the midrashic literature. Midrash Tanhuma (Emor #4), using our story as a base, states:

There are three things stated about raising someone via the Ov; the one who raises it can see it but not hear it; the one who requested it can hear him but not see him, and anyone else who is present can neither see him nor hear his voice.

It is clear that this presentation assumes the efficacy of ma’aseh Ov and also assumes that what is being “raised” is a spirit that has some real or envisioned form and some real or imagined voice such that only one specific party can see—and another one can hear—the apparition.

Since Saadiah rejects the entire enterprise of Ma’aseh Ov as being efficacious (as we will see below), he interprets the event as a resurrection, such that there is both body and voice that can be sensed by anyone present.

The second critical point in Saadiah’s interpretation is that he absolutely negates the possibility that the necromancer could have raised Shemuel—or anyone—from the dead. He accords this possibility to God alone. This is, again, a departure from the approach of the Midrashim (and Talmud); yet Saadiah does not feel bound to their interpretation if it is contrary to reason.

Saadiah’s motivation for interpreting thus is stated clearly. He is not willing to read the incident at “face value,” as an apparition is not part of his world-view, nor is he willing to interpret the entire thing as being imagined by Shaul (or some variation thereof), as that violates the straightforward reading of the text. Since we are able to interpret the entire narrative in a way that comports with reason, we will do so without having to resort to non-literal meanings of words like “he said,” “she saw,” etc.

We will reassess and complete our discussion of Saadiah’s interpretation after studying the approach of another Gaon.

R. Shemuel Ben Hofni

Shemuel b. Hofni Gaon, (d. 1034) was the last Gaon of the yeshiva in Sura. Full disclosure—he was R. Hai Gaon’s (quoted above) father-in-law. He was a noted halakhist as well as an exegete, although few of his commentaries are extant. One of the valuable tomes that we have available is his commentary to the book of Shemuel. As regards our episode, he comments:

“In reality, she did not revive; rather, the necromancer fooled Shaul….When it states “Shemuel said…” it truthfully means to say that the woman, the ba’alat Ov, told him that “behold Shemuel is telling you thus and thus.” If someone challenges this, saying that the text did not state “the woman said to Shaul that Shemuel is telling you…” we will answer him that indeed that is true, but reason dictates that in truth that’s what it means that the text is telling us what the ba’alat Ov’s words…for it isn’t reasonable that Shemuel would speak after he died and it is unreasonable that God would revive Shemuel through the office of the witch for this is against nature and is a unique power given to Nevi’im. But indeed it was she who convinced him to ask for this when she said “whom should I raise for you?” and he said “raise Shemuel for me” and she misled him to believe that she had this power. Anywhere that we see the word amar or vaydaber and it is impossible for it to be the speech of that one about whom it is written, we will interpret it there as we said in this story; but if it isn’t impossible, then we need not reinterpret every vayomer and vaydaber in a non-literal way as long as it isn’t against reason and not impossible. You see this in the language of the text: “the vine said to them” [in Yotam’s parable, Shofetim 9—YE].

It isn’t impossible to imagine that it was well-known in Israel what [Shemuel] said while still alive “and Shemuel said to him: ‘God has torn the monarchy of Beit Yisrael from you’ “and the necromancer heard of this and encountered him with this. Regarding the victory of the Pelishtim, it may be that she saw signs and indications of this from the might of the Pelishtim and the weakness of Yisrael, similarly what she said about the death of Shaul and his sons. None of this is support for “secret wisdom” [i.e. the occult practices] because she said all of it as an educated guess.”

Discussion

The fact that R. Shmuel ben Hofni is responding to at least one of R. Saadiah’s points is fairly plain to see. He overtly addresses the problem of reading vayomer Shemuel as “Shaul imagined that Shmuel had spoken with him” (through the deception of the necromancer). Saadiah had already weighed in on the issue by pointing out that we have to accept the straightforward reading of the narrative for “otherwise, we will have to revisit every mention of vayomer and vaydaber.” R. Shmuel b. Hofni responds to this by pointing out that even words as simple and common as vayomer are sometimes understood metaphorically, such as in the case of Yotam’s parable (trees don’t speak). It is up to the reader to determine how convincing a defense this is—but his entire thesis is dependent on this read of vayomer Shemuel.

Like R. Saadiah, R. Shmuel b. Hofni absolutely rejects the possible effectiveness of necromancy and he therefore finds it necessary to interpret the narrative differently from Haza”l. Unlike R. Saadiah, however, he is willing to go much further with the story and read the entire scene as a deception. Here is how Rada”k reports his comments:

…Shemuel didn’t speak with Shaul, and Heaven forbid that Shemuel would have ascended from his grave or speak, but the woman did all of it deceptively. She immediately recognized that [her client] was Shaul but to try to show him that she had “the wisdom” and that was how she recognized him and identified him she said “why did you fool me, yet you are Shaul!” It is the manner of the ba’alat Ov to place a person who speaks from a hiding place in a quiet voice and when Shaul came to make his request of her and she saw him upset and she knew that he was going out to war on the morrow and that all of Israel were greatly afraid and she knew what Shaul had done when he killed the Kohanim of Nov, she fed the “speaker” the words that we find in the story. As to when it says “and Shemuel said to Shaul”—that is what Shaul thought to be the case, for he thought that Shemuel was speaking to him. As to what “he” said: “And you didn’t fulfill God’s anger against Amalek,” the matter was known that from that moment Shemuel had said to him “He has rejected you from being king”. Regarding what “he” said: “[He gave your kingdom] to your fellow, David” it was known throughout Israel that David had been anointed as king. When “he” said: “tomorrow you and your sons will be with me,” “he” said following reason [i.e. it stood to reason that they would die in battle, given the odds, etc.]. This is the commentary of R. Shmuel b. Hofni haGaon z”l and he added that even though the sense of the words of Haza”l in the Gemara is that the women really resurrected Shemuel, these words aren’t to be accepted where this a logical refutation.

The lines are quite clear—whereas the talmudic tradition and the post-Geonic mainstream read the story as literal, these two Geonim (along with R. Hai, who adopted R. Saadiah’s approach) rejected a literal read based on reasoning, maintaining that necromancy (and the other black arts) were all vanity and foolishness. This metaphysical principle (if we might call it that) drove their interpretive strategies. The one point which divided R. Shemuel b. Hofni from his esteemed predecessor (and his own son-in-law) was the impact of taking Shemuel completely out of the equation; even though it impacts on the way that the entire passage is read, the consideration is a relatively minor one—relative to the macro question of the efficacy of the black arts. Note that both of our commentators explicitly address themselves to talmudic interpretations and reject them due to their not conforming to reason.

The foundational question I’d like to address in this final section is what caused these sages to turn their philosophical backs on the Babylonian (and Palestinian) tradition of spirits, the reality of the occult and so much more.

- The Geonic Period

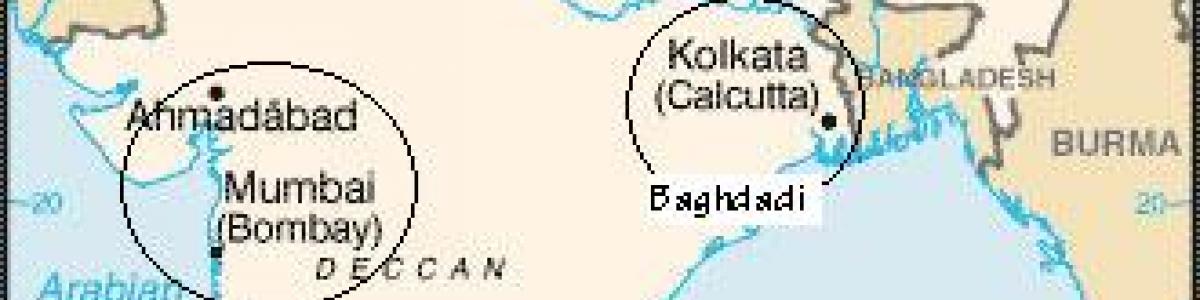

The Geonic period, from roughly the middle of the ninth century through the middle of the eleventh century, was a time of significant changes affecting the Jewish community. There was little question as to where the center of Torah learning and erudition was—every question of ritual, history of Torah transmission, proper practice and attitudes posed during these two centuries by any Jewish community, from North Africa through the Iberian peninsula was addressed to the “two yeshivot,” housed in Baghdad. The academies of Sura and Pumbedita had been uprooted from their eponymous towns and moved to the newly founded caliphate center. Although a significant percentage of the Geonic literature that was available to us until the end of the nineteenth century was made available via secondary sources (e.g. quoted in the literature of the Rishonim), a literal treasure trove of responsa, commentaries, codes and more was unearthed with the discovery of the Cairo Genizah. That immense storehouse has done more to open our eyes to that era, including much about the world in which the Geonim lives and their challenges, both from within and from without.

Of the challenges which speak most directly to our issues, two presented the rabbinic leadership with unprecedented situations and called for unprecedented responses.

A Note on the Flexible Nature of the Jewish Community and Leadership

One of the hallmarks of Judaism throughout its evolving millennia is its ability to stay true to its mission and to the ideal of declaring God’s Unity at the cost of comfort (exile) or even at the cost of life (martyrdom). Balancing this staunch commitment entails the ability to flexibly shift and adjust to new conditions.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this takes us 1,200 years before the era under question. In 539 bce, the Jewish communities from east of Babylonia through Israel came under the rule of the Persian Empire. Until this point, the Jews had either been independent and sovereign (e.g. the David era) or completely subjugated (e.g. the Babylonian exile). For the first time in history, the Jewish people were autonomous but not sovereign. This means that they had rights, including the right of redress, had standing in the Persian courts and had representatives to the court. As a result, they had to learn to speak the language of the court (Aramaic), to use the pagan month-names (e.g. Nisan, Iyar) used by the Persian court (for dating documents) and had to use the Aramaic script in use in the court (instead of the Hebrew script they had used since the introduction of writing). In other words, issues that were felt to be non-essential to Jewish identity, mission and belief were “negotiable” in order to be able to survive and thrive in their new surroundings.

It may be argued that a parallel transformation took place at the tail end of the Hellenistic era, after the kulturkampf that led to the Hasmonean revolt was no longer an issue. The mode of traditional study and Halakhic instruction shifted from the prophetic mode to the system of discussion, debate, prooftext vs. prooftext and argument vs. argument that we know as the Midrash Halakhah and, later, as the Talmud. This shift seems to sit at the heart of the sugya of “Tanuro Shel Akhnai” (BT Bava Metzia 59b) where R. Eliezer, representing the “old way” is rebuffed and ultimately excommunicated by the “new generation,” led by R. Yehoshua, whose brilliant use of the phrase “it is not in heaven” is used to support the methodology of thrust and parry, proof and disproof—all of which are hallmarks of the Greek method of discussion.

Babylonia (Iraq): The New Norm (Eighth–Tenth Centuries)

The Geonic era brought a similar change. The Jewish people had never been in an environment of free inquiry, of philosophic discourse among members of “competing” religions and of scientific thought. Even though the Jews had had interactions—not all belligerent—with the Greeks in the fourth century bce through the first century ce, they were not (for the most part) of a philosophic, speculative type. Witness the few such interactions (whose historicity is not at all assured) between “the sages of Israel” and “the sages of Athens” or the Aggadah about R. Yehoshua b. Hananya and the wise men of Greece (BT Bekhorot 8–9). The rabbis’ adoption of Greek methods of argumentation speaks to exactly that and no more—method, but not axioms.

After centuries of life in Sassanian Persia, with an up-and-down relationship with the monarch but a decidedly antagonistic one with the religious Habar priests of the reigning Zoroastrian faith,[9] the Islamic era of the eighth to tenth centuries ushered in a revolutionary period of philosophic inquiry and free intercourse between representatives of Islam, Christianity and Judaism. The premises for the discussions, dialogues and debates where philosophic principles which could be argued without recourse to Scripture (which, of course, could not be adduced as proof against someone who does not subscribe to the sanctity of that Scripture). Much of this was generated by the appearance of the Kalam school, whose teachers, the mutakallimun, a school which arose in the middle of the eighth century as a means of developing arguments against detractors and doubters of the fledgling Islamic faith. This mode of inquiry, using rational and universally accessible argument to promote religious doctrine was a first—at least as far as the Jewish polity was concerned. Even though the Kalam began as a means of rebutting Jewish (and Christian) arguments, the mode of thinking and rhetoric spread in this relatively open society and was adopted by both Christian as well as Jewish thinkers. It is clear from his writings that Saadiah’s approach was significantly impacted and driven by the Kalam. Even though both Saadiah and Maimonides rejected the arguments and conclusions of the mutakallimun, this new frame of thinking and style of expression became the norm.

This should not be perceived as such a surprising move; as illustrated above, Jews have, when possible, engaged in cultural conversation with the “other” and have often been influenced as much (if not more) as they have impacted. As stated above, the core ideals and commitment to halakha do not waver—but there are entire worlds that revolve around this core existence that move and shift along with Am Yisrael’s changed circumstances.[10]

It is important to keep in mind that the “traditional” Babylonian beliefs in demons, spirits and the like were never seen as religious doctrines; they were all perceived as “reality.” Just as modern man accepts the existence of microbes, bacteria and the like—and they all help to explain the phenomena that we experience—people living during the rabbinic era assumed the existence of demonic beings who were responsible for “the crowding at the Kallah…knees that are tired…clothes of the students that wear out….”[11] This would be just as true about the existence of spirits who outlive their physical lives and continue to visit earth in that form and who (in spirit form) could be contacted.

This entire frame of reference shifted in the post-Kalamite era and those who were engaged in these interactions and in study were quick to eschew the entire other-worldly existence of demons and the like, along with spirits independent of their bodies. As such, the only way that the episode at En-Dor could be explained would be via resurrection—body and soul together; based on hard-core philosophic standards and the intensified monotheism that came with it, this was seen as an act that only God Himself could produce. Saadiah and Shemuel b. Hofni took these premises in two different directions—based on their consideration about the “slippery slope” of interpreting the simple word vayomer as anything but literal.

To put it simply—as much as (even) a Hakham of the Amoraic era, such as Rava (BT Berakhot 6a) would assume the existence of the “spirit world” around him—by the tenth century in Iraq, rabbis (such as Saadiah) would utterly reject that point of view and would explain phenomena in a way that accorded with their thought system.[12] They would regard it as most modern traditional Jews view the medical advice in the Talmud—as the best way that that era had of diagnosing and curing—but not reflecting any theological truth that must be maintained at the cost of reason.

“A Wise and Discerning Nation”

One final word about the cultural shifts outlined here, of which the Geonic “revolution” is only one. Although we know nothing about prophets or early sages engaging in mathematical or astronomic calculations, by the time we get to third-century Eretz Yisrael, no less an authority than Bar Kappara (student of R. Yehudah haNassi) would be quoted as follows:

Rabbi Shimon ben Pazi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said in the name of bar Kappara: Anyone who knows how to calculate astronomical seasons and the movement of constellations and does not do so, the verse says about him: “They do not take notice of the work of God, and they do not see His handiwork” (Isaiah 5:12). And Rabbi Shemuel bar Naḥmani said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: From where is it derived that there is a mitzva incumbent upon a person to calculate astronomical seasons and the movement of constellations? As it was stated: “And you shall guard and perform, for it is your wisdom and understanding in the eyes of the nations” (Deuteronomy 4:6). What wisdom and understanding is there in the Torah that is in the eyes of the nations, i.e., appreciated and recognized by all? You must say: This is the calculation of astronomical seasons and the movement of constellations, as the calculation of experts is witnessed by all. (BT Shabbat 75a)

In other words, there was an understanding that the statement in Devarim that the nations of the world would exclaim “what a wise and discerning nation” was not merely descriptive—it was also prescriptive and obligated Am Yisrael to constantly maintain an image of being at the forefront of mathematical, scientific and, we would argue, theologico-philosophical thinking. Am Yisrael should never be seen as “backwards,” “primitive” and the like and anyone who has the ability to demonstrate the wisdom which we have been granted has an obligation to engage in it.

I believe that this sentiment has played a central role in Jewish cultural-methodological flexibility throughout the millennia and was part of the unstated (and perhaps, subconscious) adoption by the Geonim of the new, rationalistic modes of thinking that swept through the high culture of tenth-century Bavel.

For Further Study:

Wolfson, Harry Austryn, 1887–1974. Repercussions of the Kalam in Jewish philosophy 1979.

Nemoy, Leon: Al-Qirqisani on the Occult Sciences: Jewish Quarterly Review, 76/4, pp. 329–367.

[2] At this point, it seems that the “raise up” motif is no mere idiom—she “saw” Shmuel coming up from out of the earth! Shmuel also complains (ahead, v. 15) about being brought up (lha’alot oti).

[3] In what office is Shaul looking to Shmuel? Since God hasn’t answered him through the prophets—what different position does Shmuel occupy at this point?

[4] This “feebleminded” approach is the one adopted, nearly verbatim, by Ramban—see also in his commentary to Devarim 18:9.

[5] R. Shmuel b. Hofni Gaon as quoted in Otzar haGeonim, vol. 4, Hagigah, Teshuvot #5 (p. 4).

[6] Simha Assaf, MiSifrut haGeonim (1933) p. 155.

[7] It is an abbreviation of the title: “Ge’on Yaakov, Reish Metivta”. The word, as used there, means “pride” (see Tehillim 47:5).

[8] The interested reader is directed to Prof. Brody’s biographies of R. Saadiah, available in both English and Hebrew.

[9] See inter alii, BT Shabbat 11a, ibid. 45a.

[10] Witness the dramatic shift to the study of pshat in 12th c. France, the newfound interest and emphasis on the study of grammar in eleventh-century Spain or the suddenly rekindled interest in Tanakh itself in nineteenth-century Germany—all of which came on the heels of trends in the general society of each of these eras and places.

[12] And, to briefly respond to a question raised above, as Am Yisrael was either segregated or moved into a cultural domain which placed little emphasis on this form of thought (e.g. Ashkenaz), the motivation for adopting a rationalist approach abated and other, fresher (yet seemingly older) modes of thought made their way into the rabbinic consciousness—and all of that gave birth to its own movements, such as Hasidut Ashkenaz and, later, the mysticism of the Lurianic school. All of this is significantly beyond the scope of this paper, but the interested reader is encouraged to follow these stars.